Some will recall that at column’s end, my Uncle Mike — the youngest child of diarist and Pvt. Mark Stafford — is pondering at age 86 whether the alcoholism that left him a shell of a father had been caused by the trauma experienced by the artilleryman who fired and dodged artillery shells during his “days of sport” in the war’s final battle.

I wondered, of course, whether the same forces cut his life short and left us not a crumb of memories to compare to the rich ones we still feast on about our Grandpa Salli.

As is often the case, one of the bottles that came flying at me with a message involved reporter’s regret. Only on a post-deadline search did I discovered that the World War I Battle of the Somme had produced, in all, a million-man march of wounded and dead to hospitals and graveyards with Germany’s 600,000 leading the statistical way.

More food for thought was served up to me last Sunday at Mundy’s restaurant, where my breakfast friends gather.

Between forkfuls of food, friend Doug happened to say he’d been rereading some Ernest Hemingway, a writer who experienced the violence of the 20th century’s first have as battlefield ambulance driver and war correspondent.

After nodding to the spareness of Hemingway, he told us he found the book’s characters a motley crew of shallow, self-centered drinkers and partiers in what was a boring story.

From across the table, friend Margaret, suggested that that the aimlessness of the crowd may have been Hemingway’s way of “talkin’ bout his generation” as the Baby Boomers of The Who did half a century later.

Two days after concluding that both may have been right, it struck me that Hemingway’s intention as a spokesman for his “Lost Generation” was telegraphed in the title of the first of his books I read: “In Our Time.”

While I intend and have no disrespect for the now largely vanished “Greatest Generation,” it struck me that a childhood spent watching movies and television shows focused on World War II had blocked my view of those involved in The War to End All Wars — and maybe in part because only 20 years passed until the next one.

Its surviving members endured two man-made disasters in World Wars I and II, plus the natural disaster tacked on to the first war by the Spanish flu, which went on a killing spree that eclipsed the wars.

I was trying to imagine the weight of that when my wife pointed me to a bottle with more messages: A Veterans Day PBS special, American Heart in World War I: A Carnegie Hall Tribute.

Although I feared it might be a pop-culture trivialization, the show served up the lively tunes of the time without hiding the horrific history using as historic tour guides a handful of individuals whose hearts bodies and minds were forever changed while “over there.”

Among them was former President Theodore and Edith Roosevelt’s youngest son, Quentin, whose life seemed to burn so brightly and at 20 crashed and burned during a World War I dogfight. This broke not only their hearts, but the heart of Quentin’s sweetheart, Flora Whitney, an heiress of the Vanderbilts whose family’s Biltmore Estate will draw a throng of visitors again this season.

Baby Boomers might find a parallel to how this romantic and tragic story struck the nation in the visual memory of toddler John F. Kennedy Jr. salute to his father’s casket as the magic that had been Camelot crashed and burned.

The Carnegie Hall special also shone a light on F. Scott Fitzgerald, a writer of the Lost Generation whose fictional World War I veteran, Jay “The Great” Gatsby portrayed the Lost Generation as it stumbled into the booze-soaked parties of the post-war Jazz Age.

I remember once asking my Grandma and Mark’s wife, Agnes Stafford, about what it was like in the great Depression.

Well, there wasn’t much work, she told me, but the parties were fun.

Which brings us to the inscription of my grandfather’s diary, which comes just before his first entry notes that he enlisted on his girlfriend Agnes’ birthday.

With the diary’s cover shut, the message kisses the lines on the facing page on which Mark penned his name and rank in Battery A of the Second Battalion assigned to the French Artillery while serving with the American Expeditionary Force.

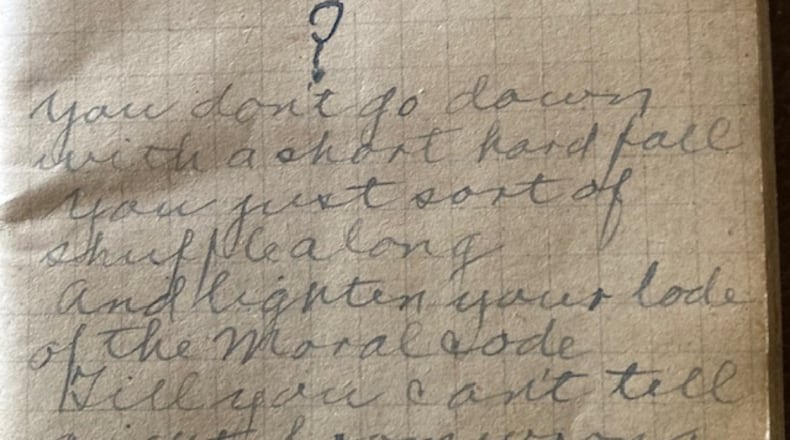

In the diary, he wrote:

You don’t go down

with a short, hard fall;

You just sort of shuffle along,

And lighten your load

of the Moral code,

till you can’t tell

Right from wrong.

These lines are from “Down and Out” by Clarence Leonard Hay, a poem that first appeared in the Aug. 3, 1912 edition Collier’s Weekly magazine.

(Springfielders will want to know this was seven years before Collier’s was purchased by Crowell Publishing of Springfield.)

The poem was regularly recited at “the early Gunsite Reunion/Theodore Roosevelt Memorial gatherings.”

Coincidentally, Collier’s published it, Teddy Roosevelt brought his presidential campaign as head of the Progressive or “Bull-Moose” Party to Springfield in the run-up to Ohio’s presidential primary.

His candidacy split Republicans in the Buckeye and every other state in two, undermining the campaign of Cincinnati’s William Howard Taft and clearing the way for the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Five years later — and just one after having been narrowly re-elected — Wilson tipped the balance in World War I to Allies by deciding to send 2 million of our boys “over there.”

Among them were four Roosevelt sons and a 21-year-old from Marquette, Mich., who would keep a wartime diary.

About the Author